Today will mark the third day in a row that I will be out on my bike...I'm getting ready to leave now with Mia. We rode together two days ago on the back road out towards Robesonia and back via Blue Marsh and Bernville. Too many cars on the road, first of all, and too many of them came far too close, beeped and/or gave us the finger.

I get particularly annoyed by this, and tend to go chasing off after the car, running on adrenaline (though never catching them...and if I did, what, exactly would I do). Mia, conversely, smiles and waves. She likes to be the friendly cyclist, not wanting to anger any more the already angry driver. And give us cyclists a good name. She's probably right. But sometimes I can't help myself. Like two days ago when a woman tried to pass us on a one-lane road, got caught out when an oncoming car was coming the other direction, and rather than get mad at herself for being in a hurry, honked at us and flipped us off. I chased her down for a while, keeping pace (there was a slow-moving dump truck in front of her), but never catching up.

Anyway, I read a very good article in TIME this morning (see the link here), talking exactly about what I have been annoyed by - namely that cyclists have a RIGHT to share the road, and that motorists just don't give us any respect. We are allowed to ride two-wide (it's safer, actually, as the cars are forced to wait for a clear passing lane rather than squeeze us onto the shoulder if we'd been riding single-file). Cars are supposed to give cyclists a three-foot wide margin on the road. That rarely happens. but when it does, I smile and wave honestly, as the nice cars are the rare ones.

So, below is the text of the TIME article. Give us a break. Learn the law. If a car hits and kills a cyclist, it likely won't be the cyclists problem - he'll be dead - and the driver might wind up in jail. It's not worth saving the extra few seconds. Plus, what's wrong with being friendly?

-----

Monday, Jul. 16, 2012

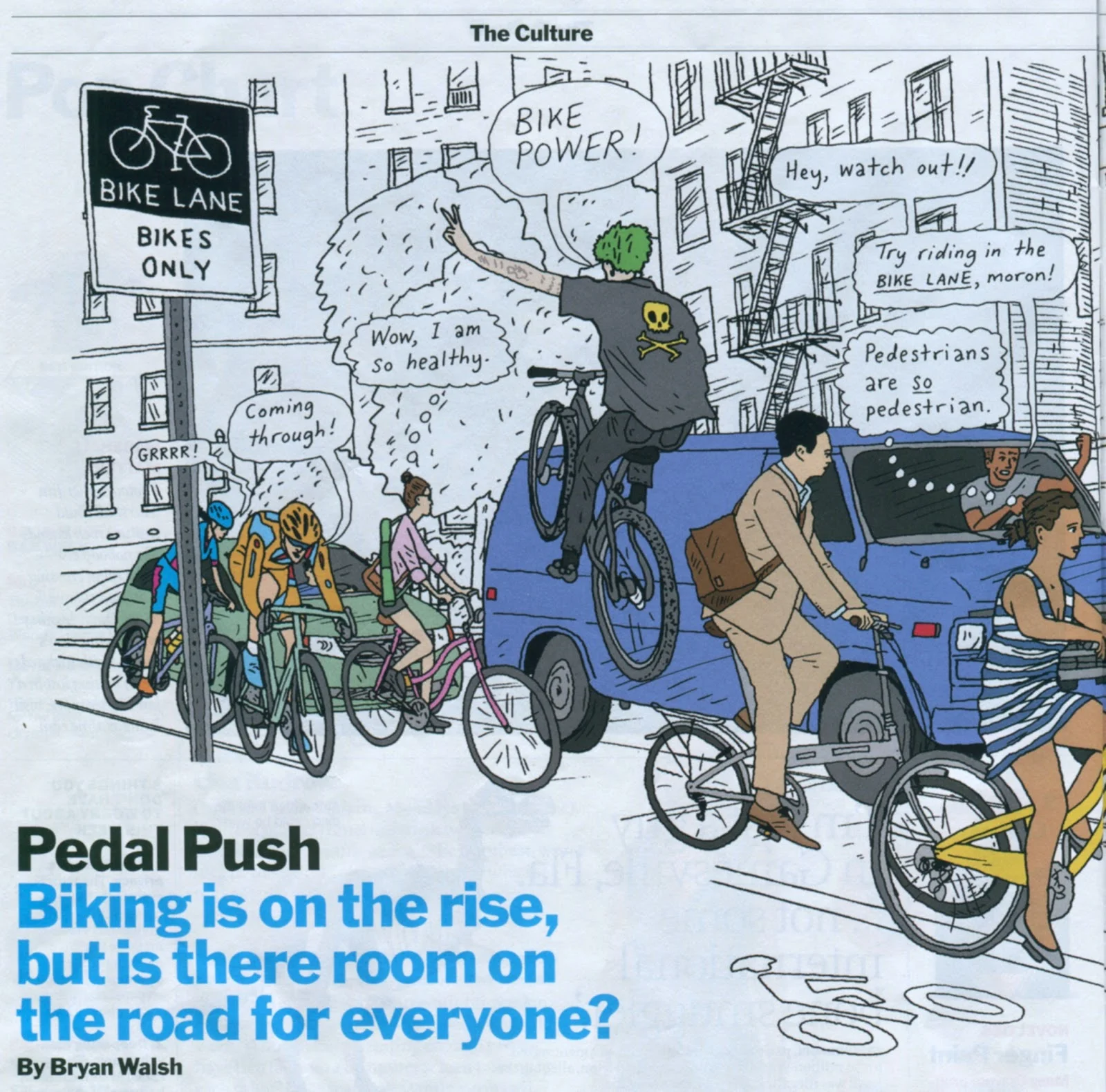

Pedal Push

By Bryan Walsh

Jeff Frings has a talent for attracting insults. Soda bottles have been hurled at his head without warning. He's been called unprintable names by people who don't know his actual name. He's been sideswiped and rear-ended and run off the road more times than he can count. Red Sox fans wandering through Yankee Stadium have been subject to less abuse from complete strangers than Frings has on the streets of his hometown, Milwaukee.

So what's his problem? It's simple: he's an avid bicyclist. Over the past few years, Frings--a 46-year-old photographer who bikes well over 100 miles a week--has kept video of his rides, taken from cameras mounted on his helmet and his handlebars, because he wanted visual evidence of his encounters with aggressive drivers. (He now uploads the video to his website bikesafer.blogspot.com. Frings has suffered more than a few injuries in scrapes with cars, but what really stands out is the gratuitous hostility. It's not just that inattentive drivers fail to give him the three feet of space required by law. It's that they're galled by his very presence. "They think that you don't belong on the road," says Frings, "and they're trying to teach you a lesson."

In many ways, there's never been a better time to be a bicyclist in the U.S. After decades of postwar decline--matched by the rise of the car--the number of Americans biking regularly has been increasing steadily over several years. More and more people are using bikes to commute to work and just to get around, in cities such as Washington and Minneapolis, which have some of the country's highest cycling rates. Progressive mayors in Chicago, San Francisco and elsewhere have been laying down bike lanes and replacing car parking spaces with bike racks. Bike shares, which lend out two-wheelers for short trips at low fees, are blossoming around the U.S., with a 10,000-bike program sponsored by Citibank launching in New York City this month.

But even in the most pedal-friendly cities, cyclists can still feel they're biking against traffic, legally and culturally. It's as if just enough Americans have started cycling to prompt a backlash--call it a bikelash--as drivers and pedestrians ally against these rebels usurping precious traffic space. Is there room on the road for everyone?

There's no more contested space to explore that question than New York, which almost certainly has the most crowded streets in the U.S. Though New Yorkers ride the nation's most extensive transit system, more than 600,000 cars crawl into lower Manhattan each day, leading to miserable congestion. "All that traffic has a major economic cost," says transport analyst Charles Komanoff.

One way to relieve some of that congestion--while improving public health and cutting greenhouse-gas emissions--is to take people out of cars and put them onto bikes. So over the past several years, Mayor Michael Bloomberg's department of transportation has set about trying to make New York into a bike-friendly city. It hasn't been easy. For years, only semi-psychotic bike messengers and minimum-wage-earning deliverymen would brave the asphalt jungle on two wheels. But what Mayor Mike wants, Mayor Mike usually gets. More than 290 miles of bike paths have appeared under Bloomberg's administration (for a total of 700 miles), including segregated, protected lanes on major streets like Manhattan's Ninth Avenue. The new Citi Bike system, with 600 stations around town, is modeled after successful programs like the Capital Bikeshare in Washington and the Velib in Paris, which have significantly boosted cycling rates. A recent survey estimated that the D.C. program reduced driving miles per year by nearly 5 million. As full-time cyclist and part-time musician David Byrne wrote recently, "This system is not geared for leisurely rides ... This is for getting around."

A 'Crazed Campaign'

Bloomberg's policies--implemented by his high-profile transportation commissioner, Janette Sadik Khan--have produced results. More than twice as many New Yorkers commuted to work by bike in 2011 as in 2006 (rising to nearly 19,000 from 8,300). But drivers have pushed back against the bike lanes, which take away precious road space in a city where parking can be an exercise in frustration. And many pedestrians have complained about a plague of cyclists whizzing over sidewalks and through stop signs. The reliably right-wing New York Post labeled the bike-lane expansion as a "crazed campaign," while a 2011 study found that more than 500 New York pedestrians a year make hospital trips after being hit by bikes. "The rush to place 10,000 bicycles on our streets risks significantly exacerbating the number of injuries and fatalities of both bikers and pedestrians," said New York City comptroller John Liu in a press conference at the end of June.

A deeper drill into the numbers, however, reveals that cyclists are far more threatened than threatening. A study by Monash University in Australia that looked at driver-cyclist collisions found that nearly 90% of cyclists had been traveling in a safe and legal manner just before crashes, while vehicle drivers were at fault for more than 80% of the collisions. A 2011 study of Barcelona's bike-sharing program found a tiny increase in the risk of death from traffic accidents, but one that was more than balanced out by deaths that were prevented as a result of the health benefits of regular cycling.

Even cyclists admit that some of their ilk can be maddeningly mercurial, blowing through intersections and weaving through traffic. But it should be pretty clear that a 20-lb. bike is considerably less dangerous than a half-ton car. Last year 241 pedestrians or cyclists were killed by motorists in New York City, yet only 17 of those drivers faced criminal charges. The New York police department--as is the case with most police forces around the country--almost never investigates a car-on-bike or car-on-pedestrian accident unless the victim dies or the driver is found to be under the influence. "If you're a cyclist who's been hit by a motorist in a couple-ton vehicle, that's like deadly assault," says former Olympic cyclist Robert Mionske, now a lawyer in Portland, Ore. "To have an officer say that there's nothing they can do is incredibly frustrating."

Creating a New Normal

So why are cyclists so hated? Blame social-identity theory. Cyclists can be dismissed as a sub-subculture, one far removed from an American mainstream defined by cars and drivers. To a driver, a cyclist is an unpredictable outsider, someone implicitly less worthy of respect--or for that matter, of space on the road. And if one biker blows a red light, that's evidence that all these outsiders are careless, whereas a lawbreaking driver isn't held up as proof that all drivers are thoughtless. (It doesn't help that the very act of driving can blunt your patience with and sympathy for those outside the climate-controlled bubble of your car.)

It's not that drivers are unusually susceptible to this kind of confirmation bias. There are simply far more drivers than bikers operating in towns and cities designed for cars. "People tend to look at the out group and overgeneralize them," says Ian Walker, a professor of traffic psychology at the University of Bath in Britain, "while you tend to underplay the differences within your own group."

The brains of the U.S.'s more than 200 million licensed drivers can't be rewired. But there are ways to ensure that bikes, cars and pedestrians can all safely use the street. In the Netherlands, for example, drivers are drilled early to watch out for cyclists on the road, and bikers enjoy physically separated lanes. (A Dutch driver is trained to reach over her body with her right hand when opening the door to exit, which allows her to check easily for any cyclists approaching from the rear.) The Netherlands isn't the only European country where bikes have become the norm. In Denmark, 18% of trips are taken by cycle, and London's bulky gray "Boris bikes," named after the city's Tory cyclist mayor, have transformed how residents get around the British capital. But Amsterdam is a two-wheeled heaven. "In America you can feel unwelcome, but in Amsterdam the system accepts you," says Andy Clark, president of the League of American Bicyclists. "You don't feel like you're outside the law."

Those rules and regulations have helped make cycling ubiquitous and safe in the Netherlands, where 26% of daily trips are by bike. But more than any law, it's that sheer number of cyclists--men and women, kids and the elderly--that really makes the difference. No U.S. city is anywhere near Amsterdam when it comes to pro-cycling policies. (Portland, Ore., where nearly 6% of people commute to work by bike, comes closest.) But as biking gathers speed across the U.S., the out group could become the in group. And maybe poor Jeff Frings will be able to ride in peace.