I'm in Oxford living in a barn.

What's nice about the barn is that is has a washer/dryer that has just finished cleaning and drying my dirty clothing that has accumulated on the boat for the past week or so.

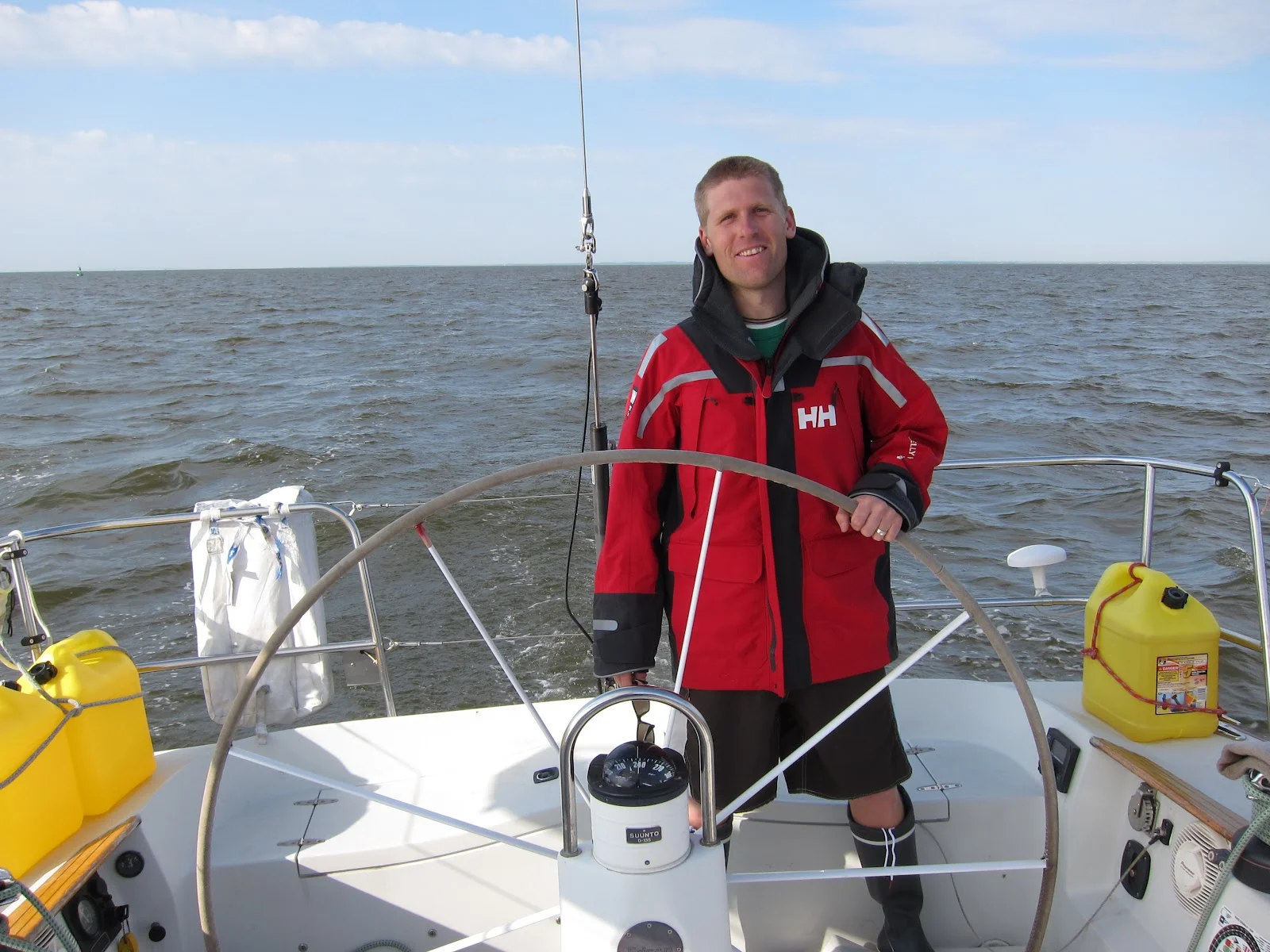

I'm here because I've been busy finding work doing whatever will make me some money and satisfy my soul, which is a difficult combination, because money does not satisfy the soul. I'm refitting Steve's "pocket rocket," his 25-foot Seaward sloop which sits in the swamp that used to be his backyard behind the barn. My front window has an extraordinary view towards the Choptank River and Chesapeake Bay beyond, and I have about 5 acres of land on the peaceful eastern shore to myself for the next few days.

I haven't been writing in here for a while, and that is a shame. Ever since I started trying to get paid to write, I've neglected the outlet that has gotten me there in the first place. It's extremely frustrating, because when I think about the stories I wrote from Austria and Germany during my stay in Prague, they were written only for myself, only to relive in my mind what had been happening in my life, and there was no motive outside of that. Writing to get published has been fun, but just isn't the same. I must continue to write for myself and simply continue these streams of consciousness to keep it pure.

That said, my professional writing career is continually on the upswing. Just today I confirmed two more monthly columns, bringing the grand total to three. "All at Sea" magazine, based in the Caribbean, will be publishing my ideas on seamanship once a month starting in June. The first article will focus on catamaran sailing and how to get the best performance out of a cruising cat. July's issue will be about anchoring under sail and the joy that accompanies it. Of course, there will be a quote from Moitessier...

"Transitions Abroad," the online magazine that's been devoted to helping people discover travel (as opposed to tourism) since 1977, will be featuring my thought and ideas on "Adventure Travel." They've already published four previous, unrelated pieces about various topics from sailing to study abroad, and have agreed to give me a column on adventure. Gregory Hubbs, the editor, and I have had some enlightening email exchanges about our ideas of adventure, travel and tourism, and he has been without a doubt the best and most accesible editor I've ever dealt with in my short career.

Which leads me to my idea of adventure. I've been trying to get this on paper ever since I started thinking about my new column, which has been nearly 12 hours now! My idea of adventure is a state of mind. Anything can be adventurous if you let yourself go. Driving across the Bay Bridge and living in a barn while working on a small sailboat in peaceful natural surroundings while enjoying cleansing solitude is adventurous in my book, as much so as hiking in New Zealand. Yes, I'd rather be hiking in New Zealand, but you make the best of what you're given.

Adventure requires a lack of planning, a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants attitude where "no" is never the correct response. Think of all the opportunities you've let slip by with that simple two-letter word. A stupid yet useful example I like to use is the sale of my Range Rover. It was winter I think (at least 'wintry' outside), and I'd gotten a phone call from Johnny, a Haitian man from NYC asking me to drive the Rover up to Manhattan, sell him the car for $1200 cash, and take the Amtrak back to Philly, which he'd pay for. Of course, my instinct was to say "no" immediately and hang up the phone, which is exactly what I did. But upon reflection, I'd wanted to sell the car to avoid the expenses and create some tension and adventure in my daily life, so why not start immediately? I phoned him back and agreed to his terms, leaving instantly in a snow flurry, and driving halfway to Manhattan before telling anyone I'd left. I didn't want the opportunity to be squashed by anyone else's conservatism. We made the transaction in an alleyway near Madison Square Garden and I walked to Penn Station with a wad of $20's in my coat pocket feeling like a drug dealer. My heart was pounding - I had a smile plastered on my face too.

I guess adventure is really anything that makes your pulse race, pumps your adrenaline and forces you to exist in the present, for a moment, a week or a lifetime. I recall landing in Fiji two and a half years ago, staying in that deserted hostel in Pacific Harbor and staring at the ceiling while I listened to the 'American Analog Set' and cried inward tears of homesickness, wondering what I'd gotten myself into and why. I could not escape the present as hard as I tried, and I had a queasy feeling in my gut - not one of sickness, but one of the unknown. It took me a while to fall asleep that night, yet ironically the next day was one of the most memorable days of my life thanks to a group of recently unemployed Fijians I encountered sitting roadside under a mango tree drinking cava.

Not unrelated, about six months later I was sitting at my job in Maryland, far from that previous adventure yet experiencing a similar feeling to the one I had that night in bed. I was about to register for the Black Bear Half Ironman Triathlon in Jim Thorpe, PA. I'd raced a marathon before, competed in sports in high school, and was an exercise phanatic, but this was beyond my realm of experience. The marathon had taken me just under 4 hours to complete and was the single most difficult thing I've ever done. This Half Ironman, by my estimates, should take closer to six hours.

I was scared. That same queasy feeling I had in Fiji came right back, but I clicked the 'register' button anyway. The commitment was made, now I just needed to follow through on it. Turns out my fears were unnecessary. I won the freaking race in my age group, finishing in five hours, thiry-seven minutes, completing the greatest athletic achievement of my young life.

The point is that adventure lies in the unknown, and we as humans fear the unknown, and this fear of the unknown forces one to live in the present, really live in the present not just attempt to (in the case of true adventure, you have no choice in the matter). As it pertains to travel, and ultimately to the column I'm supposed to write, I'll have to work on that. But thinking about it these past hours has really made me remember what is important in my life, and how I need to have one of those queasy feelings pronto to get back on track and start enjoying life again, in the present.

I'm leaving for Sweden in less than three weeks. Mia is currently in Morocco, and based on our all-too-brief phone conversation today, Morocco is exactly like I imagine it and I am incredibly jealous of her good fortune in being there. I have a reasonably good idea of what my life will be like in the coming months. Yet despite the known quantities of it, there is still enough of the unknown to qualify it as an adventure. It's what keeps me going.