Caption: "In memory of all the Åland Islanders who found their graves in the ocean."

I have a habit of beginning my journal entries – the stories I write when I’m actively out traveling or sailing or actually doing something – with reminding myself of where I was when I wrote it. Setting the scene for my own memories sake I think (incidentally, that’s the main reason I write, or at least started writing – it’s pretty selfish. I enjoy the act of it. Turning on some music – this time, Smashing Pumpkin’s ‘Adore’ album – using the blackout feature in Word that makes my computer desktop black save for the white screen on which these letters appear, and sinking right into it. And the subsequent re-reading of what I’d written. I have journals like this that go back to my first experience abroad, in Costa Rica in 2004, that one written by hand, the title and a little palm tree sketch scratched into the leather surface of that particular journal’s cover with my Swiss Army knife. It’s all great stuff).

So I’m writing from the ‘sommar stuga’ in Bergö, in the northern part of mainland (sort of) Åland. This is Johanna Mattsson’s parent’s summer cottage (there’s a mouthful), Mia’s maid of honor in our wedding and whom I met in New Zealand at the same time I met Mia. Unfortunately, she can’t be here (she works in Sweden as a dentist), but her parents have been giving us a wonderful stay.

The property was handed down (as is much of the property on Åland, for it’s nearly impossible for foreigners to buy real estate here, keeping the country in the hands of the locals. And more importantly, keeping this beautiful place reasonably priced for those who grew up here) from Johanna’s grandmother on her mom’s side. It’s a small peninsula overlooking a little cove inside a larger bay. The waterside is interspersed with the typical red granite cliffs of Åland, and reedy, swampy areas where the water is shallower. They have a very small dock built into the red granite in front of the cottage, where Tryggve, Johanna’s dad, keeps his old wooden runabout moored. Just up from the waterfront is the ‘bastu’ (sauna), which has an attached shower and a set of bunk beds for guests (where Mia and I slept last night to get off the boat). Behind the cottage is another tiny little ‘stuga’, which houses the washing machine (no dryer), larger refrigerator and the oven (the cottage itself is not much bigger than a typical college dorm room, so there is room for only a tiny fridge and simple two-burner stove next to the single sink). Next to it is the outhouse (yep). Inside, the cottage has a small dining table for two, a sitting room with a couple bookshelves and a wood stove as the centerpiece, and two very small attached bedrooms (by which I mean, literally, rooms big enough only for the beds that occupy them. No walk-in closets here).

All the buildings on this little piece of land (it’s probably an acre, if that, but a gorgeous acre it is) are painted dark green, so they blend right into the surrounding forest. The deck out front of the cottage is painted dark brown, and probably has a larger footprint than the cottage itself, with a big dining table for 6 or 8, and a handful of sitting chairs and coffee tables. It overlooks the dock just down the sloping front yard, which is mostly grass with a few big natural granite slabs poking up here and there. This is a summer place, and most of the time is spent here outside.

Arcturus is anchored in the tiny cove just off the dock, and it became apparent last night that a large sailboat is indeed an odd sight around these parts. Granted, we were able to get here reasonably easy enough from the open sea and the outer archipelago, winding our way through a couple of cliff-lined narrow channels (Mia and I tacked through one particularly small part, with 100’ red cliffs on each side, that dropped another 160’ sheer into the sea, the wind funneling directly into this little canyon. We only had a couple hundred yards room, just enough to get up some headway to enable us to tack over again. Arcturus is not the most weatherly boat – a modern J boat could probably have made it in two tacks – but we made it through nonetheless, dropping the sails only when the channel became too rock-strewn and narrow to even make one tack). But the thing is, it feels inland here. It is only 5 feet deep where we're anchored, and small fishing boats passed us as we made our way in, and the reedy, forested shorelines were a decided change from the rocky outcroppings of the archipelago.

The boat drew attention from the neighbors apparently, too. We sat down for dinner last night on the deck (I was the grillmaster for the pork loin and zucchini – only after, of course, Mia and I had a naked swim in the cove and a fantastic sauna and shower afterwards. It feels so luxurious to me, but not having a sauna in Finland is like not having a shower in America – it’s just how it works here), and shortly thereafter two of the neighbors wandered down to inquire about the sailboat in the harbor. Tryggve offered them cold beers as a good host, and they sat down for a chat. Tryggve is very impressed that we sailed all the way here from America, and is constantly asking me what this and that is like back home. He rowed out the boat with me yesterday to help retrofit the propane system from American to European. He enthusiastically told his neighbors about us and the boat, much to his delight.

Turns out that one of them (I forget their names – these Finnish ones are hard for me to understand, and harder for me to remember) was a seaman on a ship in Gustav Erikson’s fleet back in the day, and had been across the Atlantic himself several times as a merchant mariner. Gustav Erikson is rather famous around these parts, for he owned 17 of the last merchant sailing ships to sail the grain route from Australia to England, and many Ålander’s were captains and crew, far more than the countries tiny population of 28,000 would think to have provided.

Later that evening another neighbor turned up, this time in an old wooden motor launch. We watched him approach the dock from the deck, Tryggve already bragging for the man about the boat, making sure I noted how smoothly it parted the water, ‘like a swan,’ he’d said. Claes (his name I remembered) shouted for Tryggve to come down to the dock. He grabbed a cold beer first, and I followed him down, intrigued to see this neat old wooden boat. As they chatted, I asked in Swedish if I could climb onboard and poke around. ‘Absolutely!’ Claes replied.

‘Start her up!’ he said in Swedish. No, no, I can’t do that, I said. The engine was ancient, a small green two-cylinder gasoline motor built in the 1940s. The boat itself was older, build of fir on the neighboring island of Föglö in 1938, with tarred frames inside and a varnished hull outside, built in the clinker style.

Claes finally convinced me to turn the key and bring the thing to life, which I did with delight, and he eventually convinced me to take the boat out for a spin in the bay. By now Mia had come down to see what all the commotion was, with her camera in tow as usual, and the two of us took the little Adele out for a ride in the bay. The controls were directly on the engine itself, a lever (cleverly homemade by Claes from an old piston) attached to the gearbox for forward and reverse, the throttle adjacent. You had to keep the cover off the engine box to drive the thing, and you steered with a tiller. I’d never driven a proper wooden boat before, so it was a thrill. It was an open launch, about 25’ long perhaps, a beautiful canoe stern and graceful sheer. A real boat, which I made sure Claes knew I understood upon our return. He seemed proud to have shared it with us.

Later on, after the sun had set and we’d retired into the stuga, Claes came up from the dock to politely interrupt Mia and I from checking email and Facebook. I gladly closed the computer for him, and we chatted for another 30 minutes. He seemed as excited to meet us as I was to meet him, and was thrilled that we’d sailed Arcturus here all the way from America, and all the more impressed with my Swedish (as a quick aside, it’s incredibly nice to be able to speak the local language here. It’s opened up another side of life that I had not experienced for the first 4 years that I knew Mia. I was always on the outside, only getting the small translated parts of conversations and not able to really participate in life here. Now that I’m more or less fluent, at least conversationally, it’s like I’ve opened up another world).

Claes was yet another merchant seaman in his day, and told us of his trips round the world carrying cargo, ‘more than I can count,’ he said with a smile and that little ‘spark’ in his eye, as Mia likes to say. He talked about how he nearly relocated to New Zealand, after working for a while on the New Zealand Line between there and Australia, but came home for the sake of his three kids. ‘I’d thought about writing my memoirs one day,’ he told us in Swedish, ‘but I’d only publish them if I could guarantee that my kids wouldn’t read them!’

Claes and I spoke in Swedish, though he acknowledged that he speaks English. In his 40 years of travel on the sea, he would have had to, he explained. Claes is not unlike many Ålanders in that he’s followed a life at sea. We talked about how interesting it must have been to come from such a small island in the middle of the Baltic, which today has only 28,000 people, and to go out and see the world, to bring back those stories. Even today this continues. Åland has a top notch maritime academy in Mariehamn that caters to islanders and Finns and Swedes alike. Nowadays the seaman work on merchant ships and Norwegian ships searching for oil in the North Sea.

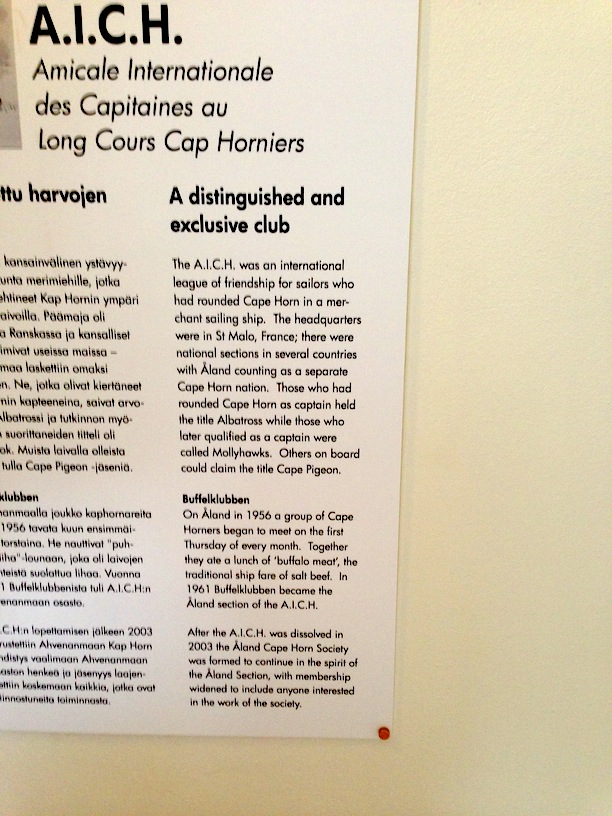

I’m saving the details of this for a magazine story, but it’s the reason that Åland controlled the very last of the merchant sailing ship trade, the reason the main flag outside the maritime museum is not that of the country, but of the International Cape Horners Association, of which Åland has an active branch (and in fact only last week hosted the International Congress, with the few remaining Cape Horners in the world coming to Mariehamn and having dinner aboard the Pommern, the only Cape Horn tall ship in the world to be preserved in it’s original state. It sailed the route up until the late 1930s). And it’s the reason we got to meet Ålands last living Cape Horner, the 95-year-old Frank Karlsson, who worked as first mate on the Viking, another of Gustav Erikson’s ships, and rounded the Horn in 1938. We found him at the old folks home in the village of Degerby, stopping there on a whim on a windy day last week, solely because I’d seen a newspaper article in the museum that mentioned he lived there. But again, I’m saving that for another story.

So until tomorrow, when we’ll sail back across the open stretch of ‘Åland’s Hav’, we’ll be enjoying the stuga, the sauna and our little swimming dock. Mia and I are planning a 13-mile run this afternoon through the countryside (the gravel roads here are paved with crushed red granite), whereby we’ll return, have a swim and a sauna, and, hopefully, another delightful dinner with Johanna’s parents. Who knows who might drop by tonight and what more stories I’ll discover.